Description

Architects often think of design narrowly, in terms of software components or a computing system that has interfacing applications that serve a bounding scope. “Whole Systems Design” considers the “whole” rather than the individual parts of a solution and emphasizes the role of interconnection between elements of the system(s), and promotes the concept of “Design as a Discipline”[1].

As an architect, taking a whole systems design approach means you must understand the entire IT environment, including the people, infrastructure, development environment and organizational structure – to name just a few. The consequences of not taking a whole systems approach to design include poor overall design efficiency (optimizing part of the system does not optimize the whole system), increased costs, decreased solution effectiveness and decreased quality attributes support.

Whole system design:

- Requires that you consider the “whole system” of interconnected elements – The “whole system” of interconnected elements that participate in, impact, and influence the design process, including the nature and rich tradition of design theory and practice, relevancy of understanding design as a discipline.

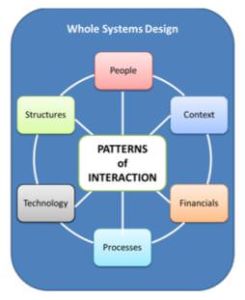

- Includes context, people, processes, structures, technology as well as patterns of interaction

- Is not a narrow definition of design only in terms of single software components or a system with integrated applications defining its scope.

- Includes the systems sciences, systems theory, and systems thinking; and involves developing a “whole systems” perspective and understanding its importance to architects; including recognizing and addressing complex systemic problems and architecture practice.

- Involves modeling as essential design action, modeling tools, and business patterns, including the importance of context and the architect’s role in the creation of a design culture.

- Requires design judgment and the construction of meaning, including work redesign, industry perspectives, and the increasing importance of architectural influence on design.

Software architecture brings together the two worlds of technology and design, and as a systems or software architect, you are a member of an emerging design profession.

[1] A discipline is a way of thinking; it is a branch of knowledge with rules of practice and established methods of conduct. A discipline is about learning.

Overview

Whole systems design requires that you consider the “whole system” of interconnected elements, including the context and the people, processes, structures, technology and other elements, as well as their patterns of interaction.

Losing sight of the “whole system” will increase the cost of delivering and supporting your solution and will likely impact the business value it provides to your organization. A critical piece of systems thinking is balancing short-term and long-term perspectives – you should design only what is necessary, but need to consider what may be necessary in the future.

Design practice follows a methodology and while the practice of design in a computing systems context may follow different methodologies than bricks and mortar architectural design, there are elements of both the “trade” and the persons that practice the trade, that are common. Design practice uses modeling and non-verbal communication media as the language of design and these “graphical” modes of thought are central to designing. Design practice uses synthesis and pattern formation as thinking tools. Different designers construe a task in different ways, which leads them to very different patterns of designing, and yet there are fundamental patterns that all designers follow:

- Design practice usually engages in collaborative (group) work. Design activities are inherently collaborative and engage those being served. In our business, our stakeholders (customers, end users, and budget holders) are engaged from the beginning in our design process.

- Design knowledge emerges from a conscious “not-knowing” and is built through reason, intuition, and imagination as elements of inquiry. This initial state of conscious “not-knowing” allows the architect to consider the whole and not be limited to what might be seen or assumed.

- Design addresses complexity yet strives for simplicity. This is truly an art. Great designers can unravel thorny problems and find solutions that seem easy.

- Design seeks to find the underlying patterns. For example, if designing a telephone system, the designer would look for patterns in how the system might be used. In what order are steps usually done? What are the relationships of different tasks and movements to each other?

- Design composes for sustainability. – Designers must always think about this. Is it designed to last?

Design maintains the whole. As architects, we must first consider the larger whole within which our solution or application must operate, and recognise that parts of a design must sometimes be sub-optimized to serve the whole system and enable its success.

As Donald Knuth once said “Premature optimization is the root of all evil”; in Whole Systems Design, the optimization or isolated design of a single component of the overall system can undermine the effectiveness of system as a whole.

Corporate Best Practices

- Ensure that Systems Design & Systems Thinking is part of the architecture curriculum.

- Establish Technical (or Solution) Architecture Review Groups to allow solutions to be reviewed by resources from all of the IT disciplines.

- Ensure architects are considering the broader context of their work regardless of the level of architecture at which they are working. For example application architects need to consider the broader context of the solution into which their application fits, solution architects need to consider the broader context of the enterprise into which their solution fits. Ensure that this broader context forms part of the organization’s expectations for Architecture Descriptions at all levels.

Sub-Components Skills

Integrative view of Architecture

Taking an “Integrative View” of architecture encompasses the systems sciences, systems theory, and systems thinking. An Integrative View of architecture means requires the development of a “whole systems” perspective and understanding its importance to architects, including recognizing and addressing complex systemic problems.

| Iasa Certification Level | Learning Objective |

|---|---|

| CITA- Foundation |

|

| CITA – Associate |

|

| CITA – Specialist |

|

| CITA – Professional |

|

Synthesis of Systems, Network and Services Design

The “whole system” of interconnected elements that participate in, impact, and influence the design process, including the nature and rich tradition of design theory and practice, relevancy of understanding design as a discipline.

| Iasa Certification Level | Learning Objective |

|---|---|

| CITA- Foundation |

|

| CITA – Associate |

|

| CITA – Specialist |

|

| CITA – Professional |

|

Design Evaluation, Redesign and Decoupling

Design judgment and the construction of meaning, including work redesign, industry perspectives, and the increasing importance of architectural influence on design. The diagnosis of design problems, unique aspects of design judgment, approaches to problem solving, and methods for unleashing creative potential.

| Iasa Certification Level | Learning Objective |

|---|---|

| CITA- Foundation |

|

| CITA – Associate |

|

| CITA – Specialist |

|

| CITA – Professional |

|

Resources

- Meadows, Donella (2008) – Thinking in Systems: A Primer

- Ackoff, R.L. (2006) – Ackoff’s best.

- Brooks, F (2010) – The Design of Design: Essays from a Computer Scientist.

- Checkland, P. (1999) – Systems thinking, systems practice.

- Cohen, J. & Stewart, I. (1994) – The collapse of chaos: Discovering simplicity in a complex world.

- Gharajedaghi, J (2011) – Systems Thinking, Third Edition: Managing Chaos and Complexity: A Platform for Designing Business Architecture.

- Lawson, B. (2000) – How designers think: The design process demystified.

Author

Sean Gordon

Sean Gordon

Technical Expert for Solution Architecture – Chevron

Sean Gordon works for Chevron (http://www.chevron.com/) where he is Technical Expert for Solution Architecture. He has over 25 years of IT experience including 10 years working for Microsoft as a consultant in Architecture and Enterprise Integration. His current focus is on developing Target Architectures for Chevron’s various asset classes.

Sean is an Honorary Lecturer at Dundee University School of Computing (http://www.computing.dundee.ac.uk/). He is also a member of the judging panel for the ScotlandIS Young Software Engineer of the Year Awards (http://www.scotlandis.com/).