What is a lifecycle

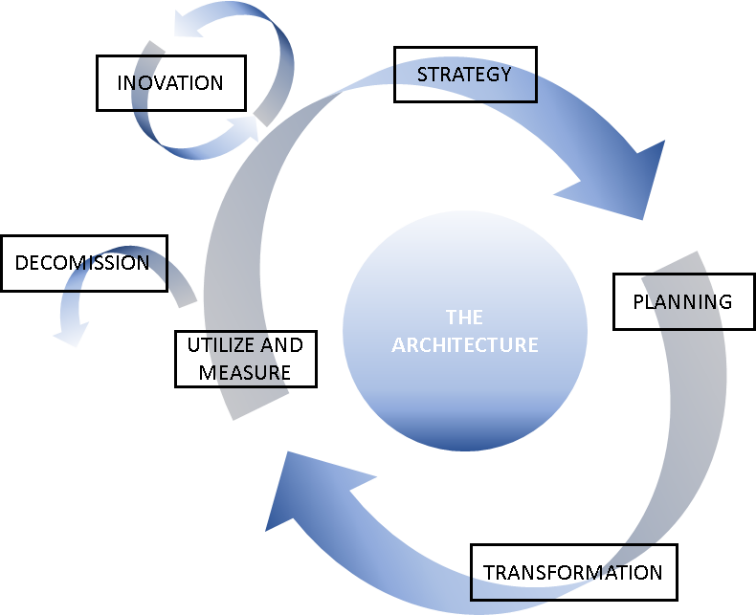

The architecture lifecycle, or Architecture Development Life Cycle (ADLC), are the stages that an architecture goes through from its inception to its decommissioning. The ADLC provides a guiding process for developing architecture, and helps the architect understand and communicate the state of the architecture.

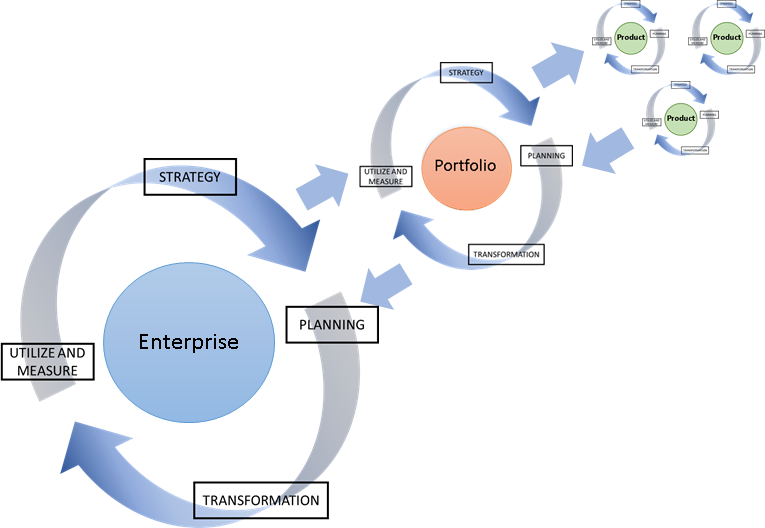

The diagram above shows the stages of the ADLC. The ADLC is an iterative cycle to ensure that the architecture develops and evolves in line with its surrounding environment.

The following are the stages of the ADLC:

- Innovation Cycle – the continuous cycle of value driven ideas for changing the business and gaining value. This continually drives the evolution of the architecture.

- Strategy– the charting of the architecture direction in the long term, and the assessment and prioritization of business cases and assignments. This results in a statement of the requirements for developing the architecture.

- Planning – given an assignment and the requirements on the architecture, the fundamental blueprints for the architecture are developed. The architecture practice or team are also assessed in terms of what is required to deliver the architecture transformation.

- Transformation – the use of the architecture in creating deliverables, such as a product or solution, which provides the sponsor with an expected value. This includes refinement of the architecture during the product or solution development.

- Utilize and Measure – the use of the architecture in practice after deployment of the deliverables. This includes measurement of the architecture to assess if it provided the expected value for the sponsor.

- Decommission – when utilization of the architecture has run its course and no longer provides value to the sponsor, the architecture may be decommissioned or replaced by another architecture.

The ADLC is a cycle which aims to continuously improve the architecture, where measurement of the architecture provides the feedback for further innovation.

Why we need the lifecycle

The ADLC provides a method including tools, deliverables and processes which help the architect develop a quality architecture. With the standard stages in the lifecycle it provides a common process between architects in developing an architecture. It helps architects communicate the status of an architecture, and to know what is required of the architect in each stage of the lifecycle.

The lifecycle helps the architect to perform architecture activities in an ordered sequence at the right stages of the lifecycle, and provides a way of communicating process in the architecture development.

Developing the ADLC itself allows the architecture practice to incorporate a standard way of working with architecture development. This facilitates an iterative and continuous improvement of architecture practices and may also provide the foundations for governance.

Lifecycle Approach

Plan the Journey

Architectures are often developed for the long term from an initial innovation through to decommissioning. Use the strategy and planning stages of the lifecycle to assess the starting point (baseline architecture), the destination (the target architecture) and any stops on the way (transition architectures). Assess if the current lifecycle provides the means to ensure that transformation is feasible and manageable. A series of iterations of the lifecycle can be planned evolving the lifecycle to meet increasingly challenging transformations.

Plan the Scope and Coverage of the Lifecycle

Consider the scope that the lifecycle will address, this will drive the tools, processes and deliverables that the lifecycle provides as support. For example, an enterprise lifecycle requires a different set of tools and processes than a lifecycle intended to support product development. The coverage of the lifecycle is also important. If the lifecycle is intended for broad coverage then the architect team has to ensure that the capacity is available to support the usage of the lifecycle.

Business Value drives the Lifecycle

The innovation cycle and the strategy phase of the ADLC are the drivers for architecture transformation. It is important at the strategy stage to show the business value that will be gained as a consequence of transforming the architecture. This creates stakeholder interest and promotes the architecture as well as helping to secure investment for any assignments.

Size DOES NOT matter

The ADLC can be applied to different scopes, single solutions or large portfolios, the lifecycle can be adapted to the required scope. The tools, processes or deliverables the architects choose to apply in the lifecycle may vary depending on the scope or the nature of the assignment.

Continuous Evolution

The ADLC allows the architect to develop the architecture, and the lifecycle itself in iterations which means that the lifecycle grows organically. With each new iteration of the lifecycle the needs of the domain can be assessed and the lifecycle adapted accordingly.

This provides a “start small, scale fast” approach and ensures that the lifecycle does not grow faster than the capacity of the architecture practice or team managing the lifecycle.

Partner the Project Management Process

The ADLC and project management process have joint interests. The project management process may rely on aspects of the ADLC to ensure successful project delivery and the ADLC may rely on the project management process to drive the architecture through the transformation. There may be commonalities in stakeholders, deliverables, resources and skills. Partnering and aligning the ADLC and project management process makes both processes stronger and can increase effectivity, both in agile and traditional methods.

Specialize the Lifecycle

As the lifecycle develops many tools, processes and deliverables can be defined in the various stages of the lifecycle. If the lifecycle evolves on a “one size fits all” principle it can be difficult for architects working in specialized architecture domains to know which parts of the lifecycle to use or why they are relevant. Instead a specialized lifecycle can be developed from existing lifecycles specifically for a particular domain (for example, high security, safety critical, telecom, medical devices). When developing a specialized lifecycle, it is important that the architecture practice or team responsible has the capacity to maintain the lifecycle and includes specialists in the given domain.

Staffing the Lifecycle

Staffing the Lifecycle When the lifecycle is adopted in a particular domain, ensure that allocation of architects is sufficient to drive the lifecycle processes, deliverables and tools. It is important that the architects have the capacity and ability to execute the lifecycle, otherwise the lifecycle may not be used correctly or at all.

Where specialist or particularly complex areas need to be addressed in the lifecycle execution, a culture of consulting can be established. This provides a way to quickly boost capacity, knowledge and increase the speed of architecture decisions over a short period of time.

Ensure the architects are trained and experienced architects. In some organizations the architect role can be filled by resources who have knowledge in technical project management, or lead developers with business skills. Neither of these provide a replacement for an architect. For example, a general doctor may know a lot about the human body, illnesses and medicines, but if we are going to perform surgery it’s the surgeon we look to.

Applying the lifecycle in practice

Innovation Cycle

The innovation cycle provides the driver of architecture transformation. This can be initiated in a number of ways, the idea written on a napkin in the restaurant, or born out of a business strategy to reach a new market.

The innovation cycle may provide the foundation for the architecture vision and plants the seeds for business cases.

Strategy

The strategy stage of the ADLC is about considering ideas for gaining value, planning the long-term development of the architecture and refining the ideas to a set of requirements which can be used to select assignments for the transformation architecture.

During the strategy stage of the lifecycle, the strategy and goals for the architecture may be reviewed, validated or updated. Business cases and assignments are born out of the innovation cycle and refined in the strategy stage. The strategy and goals of the business may determine how these are prioritized.

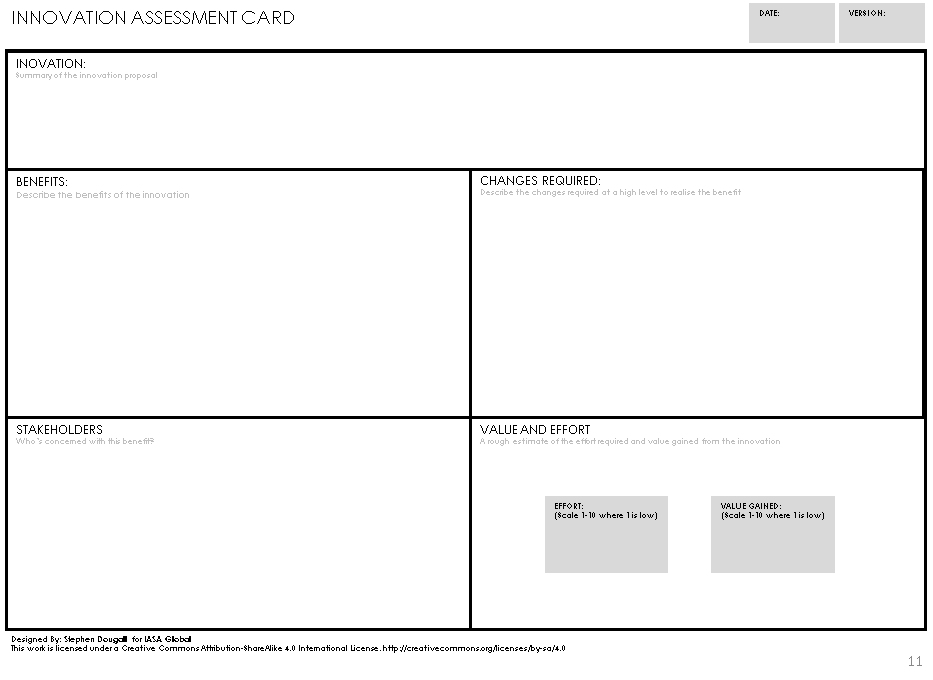

The feasibility of the ideas from the innovation cycle are verified. Many ideas may not even make it into the next stage of the lifecycle, they may lack feasibility, timing might not be right or there simply may not be investment available. To assess the feasibility of a given idea the following Innovation Assessment Card can be used.

This card can be used by teams or individuals to assess a series of ideas or innovations. The following steps describe how the card is used.

Step 1: Describe the innovation

Describe the innovation in text or present the general reasoning behind why the innovation is a good idea.

Step 2: Detail the benefits of the innovation

At a more detailed level, list the benefits of the innovation. For example, reduced cost, increased productivity, personnel motivation or greater market share. To express the benefits more clearly add “+” symbols next to each benefit to indicate how strong the benefit is.

Step 3: List the changes required

In order to realize the benefits something has to change. This can be everything from business processes, working culture, applications or infrastructure. List the significant changes that are required to realize the benefit.

Step 4: Identify the stakeholders

Stakeholders provide the influence and power to make the innovation happen. List the stakeholders that are affected by the changes or stand to make gains from the benefit.

Step 5: Estimate the Effort and Value

From the information regarding benefits, required changes and stakeholders make a rough estimate of the effort required to achieve the benefits on a scale of 1-10. For example, this may include effort to get stakeholders on-side, or the effort required to make the significant changes. Then using the collective benefits, estimate the value that may be gained on a scale of 1-10.

Innovations can then be prioritized by effort and value and result in assignments. These may even be planned for inclusion in future lifecycle iterations by creating transition architectures and a long-term target architecture. The execution of these cycles can be expressed on a strategic roadmap.

The strategy stage ultimately results in a selection of assignments and the definition of requirements for transforming architecture, these are used as a basis for the planning stage of the lifecycle.

Planning

The planning stage of the ADLC is focused on describing how to move from the baseline architecture (currently deployed architecture) to an architecture which meets the expectations of the business as expressed in the assignment and requirements.

Planning the architecture transformation involves the definition and development of the initial versions of the architecture deliverables, these describe the planned architecture. The needs of the transformation have to be assessed in terms of what is required from the architecture practice and other stakeholders.

The lifecycle itself may be assessed to ensure that it provides the necessary support for the transformation.

The planning stage delivers a definition of the expected deliverables, initial versions of some of the deliverables, and provides the resources which are sufficient for transformation to start.

Transformation

Transformation The transformation is a design intensive stage in the lifecycle where architecture deliverables are further developed and eventually delivered.

It is at this point in the lifecycle that development teams or business teams start to make the transformation from the baseline architecture to the expected architecture. The architecture continues to evolve during the transformation stage. When teams first start to use the architecture, they can uncover weaknesses, optimizations, risks, requirement changes and constraints which were not apparent during the planning stage. Therefore, the architecture can continue changing during transformation to ensure that the architecture delivers the right quality and is effective.

Equally important is to ensure that during the transformation stage the architecture is followed by the teams executing the transformation. Architects perform governance activities to support teams in following and understanding the architecture. This ensures that the critical requirements of the architecture are met, for example: legal requirements, safety requirements, security requirements. At the same time governance can act as a forum for gaining insight on the difficulties in the transformation which can lead to architecture changes.

Utilize and Measure

Once the transformation is complete the new architecture becomes the baseline architecture as it is the current state. The architecture has been deployed but just deploying the new architecture does not automatically mean that value will be achieved. The ADLC uses the utilize and measure stage to assess if the architecture provides the value that was expected at the beginning of the cycle.

The architecture may be monitored to assess if goals have been met or if the original business case has been realized. The business may have defined specific KPI (key performance indicators) which are monitored to assess just how successful the architecture deployment has been. What is to be measured may depend specifically on the value that the architecture intended to provide.

During this stage an analysis may be performed on the architecture to provide feedback into the next cycle. Measurements may be taken on factors such as automation, technical debt or even the velocity of development during utilization.

Decommissioning

Decommissioning is the final stage in the architecture lifecycle. While an architecture can iterate many cycles in the ADSL, if during the measurement stage the architecture is found to be no longer sustainable then it may be decommissioned.

When an architecture is to be phased out it should be done in an orderly fashion to reduce risk and reduce the impact of removing the architecture. During decommissioning it is important to ensure that stakeholders are aware of the phasing out of the architecture and the effects. During decommissioning the architecture deliverables may be archived and in some cases destruction of deliverables or information may be managed according to required practices. For example, sensitive information, software or hardware, may require a specific decommissioning process.

Developing the Lifecycle

Lifecycles can be developed and specialize to meet a particular business domain or culture, but all lifecycle should have one thing in common, they are developed by architects for architects. In small organizations the lifecycle may grow from a single architecture assignment with a small group of architects, where maintaining and developing the lifecycle occurs as a natural part of the architecture development.

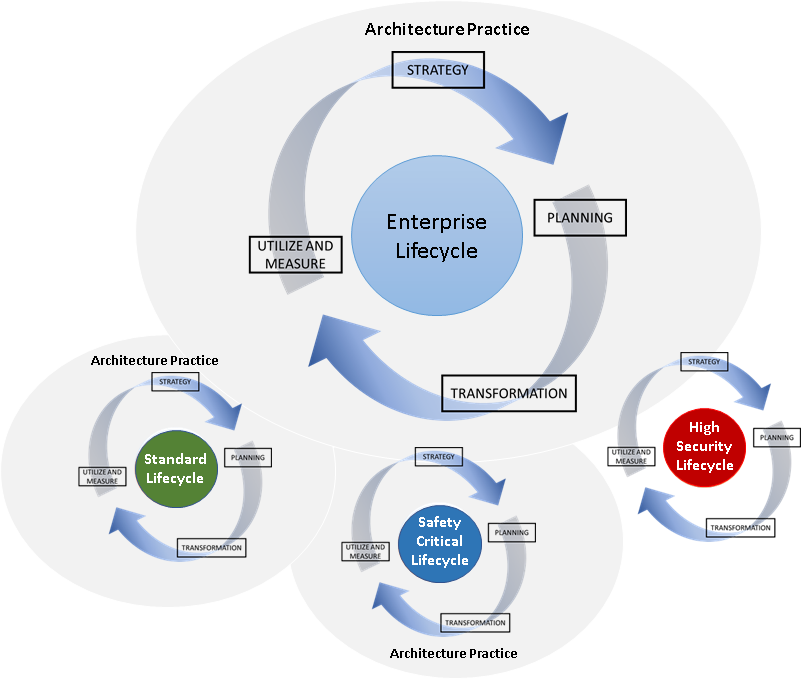

In larger organizations, as the coverage of the lifecycle spreads, the development and maintenance of the lifecycle requires more effort. This likely results in an architecture practice taking responsibility for the lifecycle. In very large organizations different business areas may place different requirements on the architecture lifecycle and may even have serval architecture practices working in different lifecycle domains. For example, in the diagram below, the organization has an enterprise practice which specializes in maintaining and developing the enterprise lifecycle. There are also two more architecture practices, one which maintains and develops the standard architecture lifecycle for developing solutions, and another which specializes in the domain of safety critical solutions. Finally, there is also a lifecycle for the high security domain which is not yet attached to an architecture practice, this may be due to the domain being in the very early stages of development where a small group of architects may be maintaining the lifecycle for a small number of solutions.

Although it can appear that these lifecycles exist in their own bubble, this is not the case. Lifecycles interact with each other exchanging outcomes, feedback and innovation for improvement, this optimizes the architecture practices of the organization as a whole.

As the adoption of the lifecycle spreads in the organization, the lifecycle itself will require development to meet the needs of the architecture practices or teams. An assessment of the lifecycle may be performed periodically or even at the start of a lifecycle iteration.

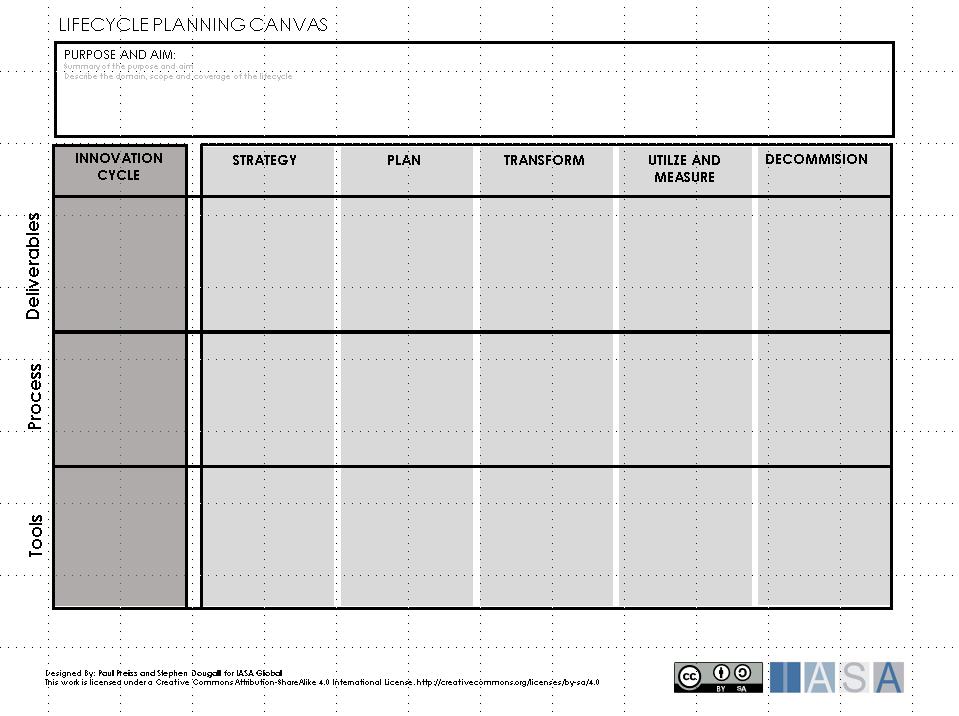

To help the architect team or practice plan lifecycle development the Lifecycle Planning Canvas can be used. It is recommended that this canvas be used in a workshop with the architecture team.

Step 1: State the purpose and aims of the lifecycle

At the beginning of the workshop the purpose of the lifecycle should be stated just to make sure participants have the same view of the lifecycle. For example, the lifecycle may be specialized to support a specific domain or scope. Sometimes the purpose and aims of the lifecycle change over time, this is why it is important to re-iterate the purpose and aim before starting the planning.

Step 2: Describe the current status

The participants write down on sticky notes the current deliverables, processes and tools which are supported in the lifecycle and then place them in the appropriate lifecycle stage. The participants can then discuss which items work well in the lifecycle, and which items do not. Items which do not work well may be subject for improvement, or simply redundant, in which case redundant items may be removed from the lifecycle.

Step 3: What is needed

With the current deliverables, processes and tools already placed on the canvas, the participants can now focus on items which are required in the lifecycle to better support architecture development. The participants write down items they think need to be added to the lifecycle and place them in the correct item category and lifecycle stage. The participants can then motivate and discuss these items until agreement is reached.

At the end of the workshop the resulting items on the canvas can be incorporated in the lifecycle. This will likely mean formally documenting the description of the lifecycle, communicating the changes out to architects or perhaps even training.

Architect-Led Adoption of the Lifecycle

Once the need for a lifecycle is established, the strategy for leading the adoption of the lifecycle should be defined. By this we mean how we spread the adoption of the lifecycle within the organization. Different organizations have different kinds of business services, products and cultures. It is important to choose a strategy that fits the organization, as this establishes a lasting impact immediately and a provides a solid base for value creation and delivery.

Two recommended approaches are the “bottom-up” or “middle-out” approach.

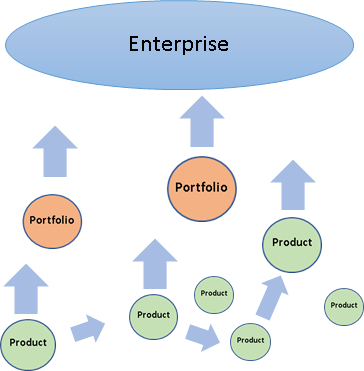

Bottom-Up

This approach focuses on adopting and developing the lifecycle around products or services. Architects focus on creating a value-based decision culture, this balances business prioritization with technology value. When using this approach, the architect often requires the ability to collaborate with architects responsible for other products or services, and requires that the architect has a good degree of technical skills. The execution and development of the lifecycle spreads from product to product moving through the organization and gaining momentum. The lifecycle is refined and improved on the collective experiences of the products or services.

This approach is often useful in organizations where technology is core to the business, the products or services, not just an enabler. Products or services often rely on technical innovation in order to gain competitive advantage. Focusing the lifecycle around the products or services brings the lifecycle closer to the source of value.

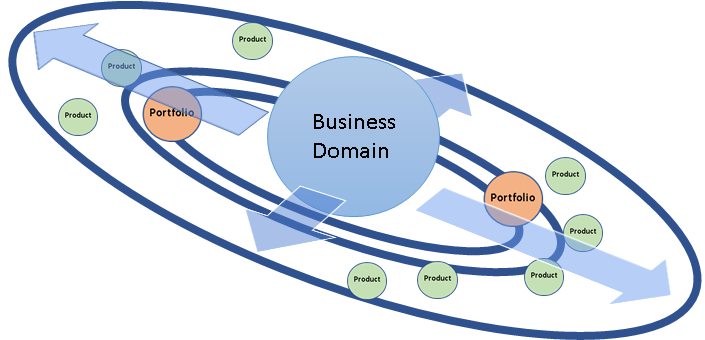

Middle-Out

The middle-out approach focuses on the business domain of the organization. Architects analyze the primary value streams of the organization and develop the lifecycle to facilitate the speedy delivery of outcomes. The lifecycle is developed at the core of the business domain, and adoption of the lifecycle spreads outwards. The architects grow their teams and stakeholders to proactively spread the lifecycle and architecture practice to more and more products and services. This approach views architects as essential in decision making and the leadership of the value stream.

This approach is often suited to organizations where technology is a facilitator or enabler in the business domain. Technology may provide optimization or enable a value stream but the technology is not often the product or service itself.

Executing the Lifecycle

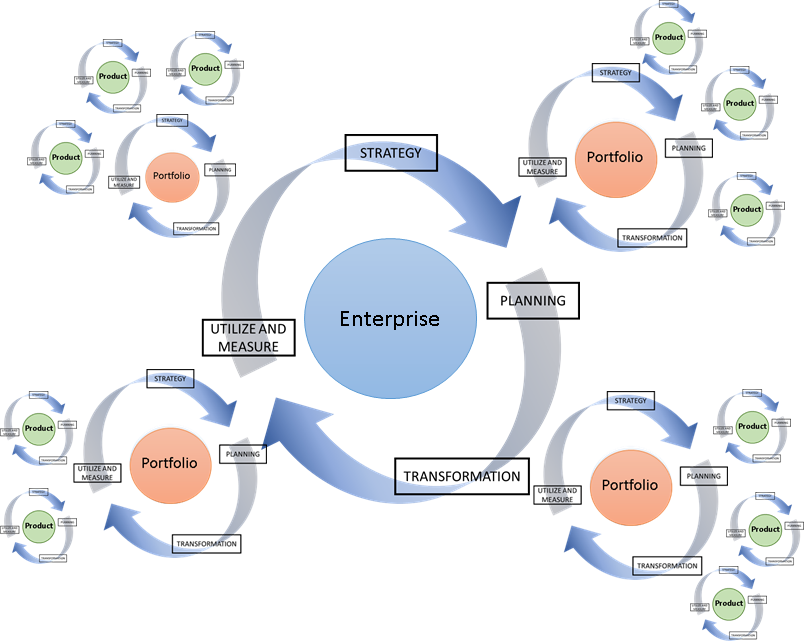

As adoption of the lifecycle spreads through the organization, many portfolios and products will be executing iterations of the lifecycle simultaneously. Depending on the product, portfolio or even the architecture assignment the iterations of the executing lifecycles will turn at different speeds. This can provide a challenge for the architecture practice in maintaining and developing the lifecycle since the scope of change increases.

In some cases, a specialization of the lifecycle may be created to address products or portfolios in different domains, this results in different types of lifecycle which may be developed and maintained separately. This can help to reduce the scope of change.

The diagram above shows an organization with three types of lifecycle: a lifecycle which is tailored to the need of the enterprise architecture practice, a lifecycle which is tailored to executing portfolios and a lifecycle which is tailored to development of products. The diagram also illustrates, for example, that the Enterprise cycle iterates at a slower speed than the product lifecycles. This is natural since a transformation at the Enterprise or Portfolio scope is likely to require that several products complete an iteration of their own lifecycle.

Lifecycle at Scale

As the lifecycle coverage increases, so does the scope of change. Since execution of lifecycle iterations all run at different speeds making changes to a lifecycle can be challenging. In this case, formal change control processes may be used to release revisions of the lifecycle, especially if there is an intention to perform governance activities. This will avoid products or portfolios having to make changes to the lifecycle in mid-iteration, which can be detrimental to the delivery of the architecture transformation.

Products or portfolios may continue with their current revision of the lifecycle during the iteration, and governance may be performed against the stated revision. When the product or portfolio have completed their iteration, they can then move to a new revision. This may also give the architecture team or practice the opportunity to test changes in the lifecycle on a limited scope before publishing lifecycle changes for full adoption.

References and further reading

TOGAF ADM

https://pubs.opengroup.org/architecture/togaf8-doc/arch/chap03.html

BTABoK 3.0 by IASA is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. Based on a work at https://btabok.iasaglobal.org/